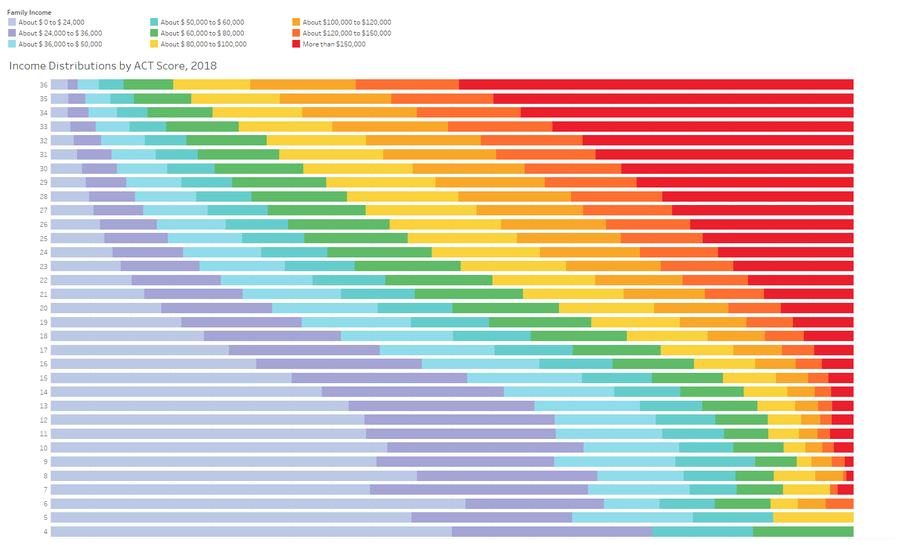

Every now and then, you encounter a graphic that powerfully illustrates a major and complex idea. This ominous rainbow chart, courtesy of the educator Jon Boeckenstedt, is, for me, one such visual.

The chart shows the family income distribution of students by ACT score. The ACT is a general college admission “aptitude” test, similar to the SAT. Just as the SAT ranges from a high of 800 to a low of 200, the ACT ranges from 36 to 4.

The point stands out so clearly you almost don’t need to say it: high scores correlate with high incomes, and low scores with low incomes. Indeed it holds, almost in lockstep, individual point by point. If you compare, say, a 28 to a 27, you will see a higher percentage of students from wealthy backgrounds with the 28 than the 27. We could almost replace the exam with a single question: what is your family income?

The same applies to the SAT. And it applies more broadly to who attends—and who graduates from—college. People from the top quartile of family income complete college at a rate 60% above those from the bottom quartile (roughly 76% versus 16%).

This is one of the main reasons that Russell Sage doesn’t use test scores in college admission. That and the reality that test scores only minimally enhance predictability of academic success from what high school grades and course selection already reveal. In short, standardized testing for college admission magnifies the advantages of family income.

What the rainbow chart lays bare is fundamental social inequity, a severe challenge to the American vision of education as a tool of social mobility. I’m proud that Russell Sage College has been recognized by U.S. News and World Reports as one of the top national colleges and universities for advancing social mobility (ranked 8 out of 389), a metric based on our success with graduating low-income students, who make up more than half of our student body.

We achieve that through the hard work of those students, talented and caring faculty and staff, small classes, and multiple forms of student support, including our new Navigate program that focuses on academic success from enrollment through graduation.

In doing so, we continue the legacy of our founder, Olivia Slocum Sage, who created a college for women when very few women even considered college. She recognized not only the social inequity but also the loss to society of not including half the population in higher education, professional employment, and government. That recognition and spirit continues in the Russell Sage College of today.

But what is frustrating is the realization that all the things we do in college–test-free admissions, educational opportunity programs, trained academic advisors, a team approach to retention, peer and professional tutoring, and so forth—don’t really get at the heart of the problem, because the sorting of students by income level has transpired for eighteen years before they ever reach us.

As those of us in higher education watch legislative deliberations, we naturally focus on the potential initiatives that most directly affect us and our students: free community college, increasing or doubling PELL grants, increased aid to HBCUs, simplification of financial aid processes, lowering of student loan interest rates, etc. And those are all important, especially doubling Pell, which could be transformative. But sitting in front of Congress is a proposal that, in my view, could do more to address the social inequity that ties college graduation to income level than anything else: two years of universal pre-K.

Yes, there is controversy about the benefits of pre-K, but evidence increasingly suggests they are significant. One important study took advantage of a situation years ago in which Boston could only provide a certain number of pre-K slots to eligible families and used a lottery system. This provided a natural comparison group of those who didn’t win the pre-K lottery. Years later, it turned out children accepted into pre-K ended up with a high-school graduation rate of 70% — six points higher than the children denied pre-K. The college attendance rate showed an even more dramatic difference: 54% of the pre-K group enrolled in college after they graduated high school, which was eight points higher than their counterparts who didn’t go to preschool.

Elizabeth Cascio’s studies have demonstrated both that low-income children benefit more from pre-K than higher-income students, and that they benefit more in universal pre-K classes than in means-tested programs. In other words, universal pre-K directly addresses the income gap in educational achievement.

An economist and former colleague of mine, Robert Lynch, has devoted much of his career to the economic argument for pre-K, asserting that high quality pre-K education more than pays for itself over time. How is it possible that the outlay of hiring thousands of certified early childhood educators and administering a universal program ends up being so much better than cost neutral?

The study by Lynch and Kavya Vaghul shows that the governmental savings come from less K-12 remediation, decreased juvenile crime and adult incarceration, and increased taxes paid by students ultimately employed with high school and college degrees. Approximately 68% of people in state prisons do not have a high school degree, as opposed to 18% of the overall adult population. So when we talk about alternative ways to address crime, increasing high school graduation rate is crucial.

But more broadly, this is a story about how to address lingering, fundamental social inequity. Like any stubborn social problem, it requires multiple approaches. I’m proud of the work Russell Sage does to make college affordable and students successful. And we are always working to be better. But it is worth reflecting on the other places in our society where we can make a difference.